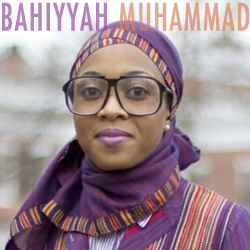

For this episode, Derek Bruff talked with Bahiyyah Muhammad, assistant professor of sociology and anthropology at Howard University. She teaches courses as part of the national Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program, courses in which half of her students are Howard students, and the other half are incarcerated individuals. Most Inside-Out courses take place at prisons, but for logistical reasons that was challenging for Bahiyyah. She turned to a set of technologies to facilitate distance learning, and to turn the course into a learning community.

Links

• Bahiyyah Muhammad’s faculty page

• @DrBMuhammad1 on Twitter

• @drmuhammad_experience on Instagram

• “Does the Apple Fall Far from Prison?,” Bahiyyah Muhammad at TEDxHowardU

• The Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program

Transcript

[00:00] [music]

Derek Bruff: [00:05] Welcome to “Leading Lines,” a podcast on educational technology from Vanderbilt University. I’m your host, Derek Bruff, director of the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching.

[00:14] I am very excited to share this interview. For this episode, I talked with Bahiyyah Muhammad, assistant professor of sociology and anthropology at Howard University. She teaches courses as part of the national Inside‑Out Prison Exchange Program, courses in which half of her students are Howard students and the other half are incarcerated individuals.

[00:34] Most Inside‑Out courses take place at prisons, but for logistical reasons, that was challenging for Bahiyyah. She turned to a set of technologies to facilitate distance learning and to turn the course into a real learning community.

[00:47] I appreciate her passion for her work, but also her intentionality in using technology to create meaningful learning experiences for all of her students.

[00:55] [background music]

Derek: [00:55] Thanks, Bahiyyah, for talking with me today. Can you first tell us a little bit about who you are, what you teach at Howard, that kind of thing?

Bahiyyah Muhammad: [01:08] I’m Bahiyyah Muhammad. I’m an assistant professor of sociology in the Criminology and Sociology Department at Howard University. I teach basically all of the criminology classes, intro to criminal justice, juvenile delinquency. My specialization, looking at a seminar on children of incarcerated parents.

[01:27] Then, of course, my Inside‑Out suite of classes, which include prisons inside‑out, juvie inside‑out which is in a juvenile detention facility, as well as policing inside‑out, where I bring students together with law enforcement officers to engage in conversations across 15 weeks.

[01:46] A lot of the courses that I teach are experiential in nature, so to speak. Then also have a heavy, heavy technology focus in terms of utilizing technology in order to implement the course from beginning to end.

Derek: [02:03] I want to mostly talk to you about your Inside‑Out programs but can you say a little bit about your Howard students who are taking these courses? Why are they taking the courses? What career paths are they pursuing?

Bahiyyah: [02:15] The Howard University students come from very diverse backgrounds, as it relates to those individuals who are interested in taking the classes. I actually have Inside‑Out classes on the undergraduate and on the graduate level.

[02:27] It’s pretty interesting, where you get a nice group of individuals. On the graduate level, these are typically students who are wanting to get their degrees in sociology but specialize in criminology. Some of them go into research. Some of them are going into think tanks, and some of them are going into academia in terms of wanting to be instructors as well.

[02:52] On the undergraduate level, it’s pretty interesting because the sociology classes are a requirement across the board. You find that you have biology students that need this social science course as a requirement and are navigating in, in that way. It’s also considered writing intensive.

[03:11] We get students that are coming in and wanting to fill that second writing requirement. You’re talking about students from the Howard Hospital, students from the Law School, students from the School of Divinity, students from School of Social Work as well as the array of departments in the College of Arts and Sciences.

[03:33] We are seeing freshmen through senior year. Students are coming from all over.

Derek: [03:40] Wow, wow, quite a variety. Some of them may be sociology majors, but a lot of them coming from all over campus.

Bahiyyah: [03:47] Yeah, the sociology majors are very interested in the course. We do find that a large percentage of them are coming in and either taking the policing side of it, or the juvenile justice side, or the adult prison side of it. Which is pretty interesting.

Derek: [04:06] That’s helpful context. Now tell me about the Inside‑Out Prison Exchange Program and how you got involved with it.

Bahiyyah: [04:12] The Inside‑Out Prison Exchange Program was started in 1997 by a professor of the name of Lori Pompa at Temple University. She took her students on a tour to a correctional facility. One of the incarcerated individual by the name, Paul. You know, Paul was so excited like any of her students do when they’re so excited about the conversation.

[04:34] In terms of motivating them and pushing them to think critically about issues that they may have not necessary considered, he asked her, “What are guys going to talk about on the bus ride back? Have you considered having something like this where you guys are coming in across the span of a semester?”

[04:54] That really resonated with Lori, and she created a full train‑the‑trainer model, pitched it to the Soros Justice Foundation and received funding from all over. Lo and behold, 20 years later, you have an international program where students are going in and out of correctional facilities all around the world.

[05:18] I myself was trained in the program in 2007. At the time I was a doctoral student at Rutgers University School of Criminal Justice.

[05:27] One of my professors, my research professor, pulled me to the side and said, “Hey, are you aware of this opportunity? It seems like this would be a perfect fit for you.” I had already had my eye on it.

[05:41] For me, it was kind of unbelievable at the time. How could you go inside of a prison and take a class across 15 weeks? When I first read it, it’s just like, “This can’t be true. This is just some information, on the Internet.”

[05:54] I started to look into it, filled out the application, ended up making it to the second round. Did an interview with Lori herself, and was accepted into the cohort for 2007. It changed my life ever since.

Derek: [06:10] Wow! What are the goals of the program? How do you structure it because you talked about going into the prisons? Tell me a little bit about what that looks like in a typical Inside‑Out course.

Bahiyyah: [06:20] A typical Inside‑Out course is an opportunity to engage in a conversation. It allows for you to teach your class in the same way that you would on campus, except the location is different. You’re going inside of a correctional facility.

[06:35] The composition of the class, though, is a bit different than what you would see on the college campus where half of the students are incarcerated, about 10 to 15 students incarcerated at whatever facility, and then 10 to 15 students at a university.

[06:51] At Howard, 15 incarcerated individuals, 15 Howard University students are going into this class to engage in whatever the topical area is. For example, when I went in and taught criminology for 15 weeks as one, we are all talking about criminological theories, the history of incarceration, prison systems, and things of that sort.

[07:16] It really is not about research. It’s not about social advocacy. It’s not about changing the criminal justice system. It really is about critical education. You find that when you go in, major transformations happen in the sense of being able to humanize both populations, so to speak.

Derek: [07:41] Can you say a little bit more about that? Like in the criminology course, what did the Howard students gain by participating in this version of a criminology course? What did the incarcerated students gain by participating in this experience?

Bahiyyah: [07:54] The incarcerated students who are considered the inside students, they benefit in various ways as well. For example, some of the individuals who participate have college credit already. Those individuals become motivated and inspired during re‑entry to apply to colleges and universities upon release, and go back.

[08:17] Some of them actually take additional programs within the institutions, for example, at American University, or Georgetown, or the University of the District of Columbia, which also offer classes at the institution. It opens them up in a way to say, “Wow, I want to take more classes.” In the same way that it does for the students at the university.

[08:37] Some individuals take it in, and they just are empowered by the knowledge, the theories, and gaining a better understanding of the criminal justice system that they’re involved in. Some of the incarcerated students have no idea about these theories that talk about why individuals who live in socially disorganized communities are faced with certain hardships.

[09:00] What strain means, and as it relates to the American dream, which is a huge theory in criminology or the middle class measuring rod. There are opportunities for them to rethink about their lives and their experiences within the framework of a theory.

[09:18] Ultimately, they go back and have conversations with their childrens and families to then inspire them to go to school, even if them themselves are not interested during release to go into an actual education program. Those are some of the ways in which the inside students have been inspired as well.

Derek: [09:39] That’s pretty amazing actually, [laughs] the way that both groups of students gain value from this experience. I want to talk a little bit about how you facilitate these types of interactions. This is a technology podcast. I’m interested in hearing about some of the technologies that you use to help facilitate this type of very unique learning community.

Bahiyyah: [09:58] That’s a great question. The Inside‑Out classes, although they’ve been around for 20 years, I am one of the only instructors that utilizes technology. I’ll tell you why.

[10:09] When you talk about transformation, it’s like, we have to be in person, that that transformation can only happen inside of a correctional facility when it’s human individuals interacting with one another in a classroom.

[10:25] If you know technology like we do, that’s not necessarily the case. You could actually bridge barriers, and build relationships, and humanize in ways that you may not necessarily be able to do in terms of human interaction.

[10:40] For my class, it really was one of the first times ever that Inside‑Out utilized technology. What I wanted to do was to create an opportunity for those students who may have been very nervous about entering a correctional facility.

[10:57] An individual who said, “I’m not signing up for this class, because I totally have no idea what I’m signing up for.” Really, to use technology to be a buffer between the students and the correctional institutions, to be that liaison or a bridge that they could go step‑by‑step until they felt comfortable with going in.

[11:18] Some of the technologies that I used, GoToMeeting. We had meetings between the incarcerated students and the Howard University students using technology. The semester that I launched the technology, I was faced with this issue. The issue was the Bureau of Prisons that agreed to partner with me for this amazing opportunity was in West Virginia.

Derek: [11:40] [laughs]

Bahiyyah: [11:42] How do you get students…

Derek: [11:45] You’re in DC. That’s like two states over.

Bahiyyah: [11:48] That’s two states over. You’re talking about a six‑hour round trip ride. You’re talking about goo‑gobs of funding, which I did not have at the time. Then 15 students on the inside and outside who are so excited about making this happen, that’s where technology came to save us all. It was a cheaper option.

[12:11] It allowed me to have a captive audience in West Virginia, sitting inside of a room in front of a camera. Then also students at a university sitting in a classroom in front of a camera.

[12:24] The GoToMeeting really allowed us to have a meeting where I used it to merge the students who were incarcerated with the Howard students in real‑time, like Skyping and having a group dialogue using technology.

[12:40] I specifically used that just to combine the students. Then I also utilized that for my office hours, two days a week for an hour. Who’s going to jump in a car and drive three hours just for office hours? Although my inside students are totally worth it, we could definitely save a lot of money and utilize technology for what it’s best at doing, connecting people in real‑time.

[13:04] I also utilized the blackboard system. Of course, I put all of the readings online. I allowed the students to be able to do virtual tours online between different facilities. If they were nervous about going into a correctional institution, they could actually have the opportunity to do that online prior to ever walking in.

[13:26] They could see what the entrance of a facility looked like without ever stepping foot in. They could engage with correctional officers using virtual technology in order to understand what that experience was like. They could actually see the inside of a cell, and you can engage with incarcerated individuals totally using virtual technology.

[13:48] I put a lot of links on Blackboard and allow for the students to be able to see the realities of what they would be faced with in the class. We also use Skype. That typically was for office hours with students at Howard, and then also with the students in the correctional institution.

[14:10] The students at Howard, believe it or not, after a class sometimes were very emotional over things that we talked about…opened up inside of them. It allowed them to be able to say Wednesdays between nine in the morning and five o’clock. They could just send me a direct message via Skype, and then we could schedule a meeting within the next 15 minutes.

[14:34] Sometimes students were on the phone in tears. I’m really wanting to walk through some of the things that we talked about inside of the institution. That could never happen in a regular classroom outside the technology. You would have to wait until the office hours or the following Wednesday, and so that was great.

[14:51] The last technology that we used was GroupMe. The students actually created a GroupMe account for the class. It allowed me to communicate with them. Also, I was silent in that group. It allowed me to also be a participant‑observer. I got to hear about the students going back and forth, texting one another saying, “Oh my God, today’s lecture was X, Y, and Z.”

[15:16] It was like I was invisible in the class. The only time I posted on there was to say, “The facility is on a lockdown. Please don’t go and jump on the Metro. Don’t come in for this day. Will follow up the next Tuesday.”

[15:31] The students, if you could see their phone, they actually had one area on the phone where all of the apps on that particular window were specifically for the class. They had the Metro app up there so that they could see if there were any delays. They had their Uber app up there so that they would be able to tap the Uber pool and be able to go with a group of three students.

[15:53] They had the Blackboard app there so that any time I sent a message or an emergency, they would get it through Blackboard, they would get it to Groupme. It really was cool. To engage with students in terms of technology, and it was great for them.

[16:09] The students are amazing when it comes to utilizing technology and having 20 windows open at one time, and engaging in conversations where they’re tweeting. They’re on Facebook, but they’re also in a class.

[16:23] It allowed them to grow in terms of their love for technology, but it also allowed me to be this amazing instructor, where I got to hear the ins and outs of what students were going through. Technology in the class has opened me and inspired me in ways that you wouldn’t imagine that it could actually do.

Derek: [16:47] I have a few follow‑ups because the cluster of technologies that you use is really fascinating. I’m also imagining, I actually visited DC last summer with my two daughters. We’re just being tourists. We’re just having fun and going to museums.

[17:05] My phone was this like a toolkit that I kept with me. If I needed an Uber, if I needed a map, if I needed to know times or phone numbers, because I think in our daily lives, we often use technology in that ways. It gives us tools to solve problems that we want to solve.

[17:21] I think sometimes in education, we think of this technology as something new, and foreign, and different, and that somehow it’s going to change how we do what we do. In our daily lives, we just pick up tools and use them more often than not. Let me ask about, so first the GoToMeeting, during class, both sets of students would get to see each other through the video conferencing.

[17:50] Were you able to have class discussion through that interface? Could the students talk to each other in a way that felt a little authentic?

Bahiyyah: [17:58] Yes and no. Yes, because we structured it in a way where the night before we did the GoToMeeting, I would send out a sheet of paper. On that sheet of paper, it would say step one through step five.

[18:15] I’ve really operationalized exactly how every minute of the conversation would go. They knew that this was the outline for what the lecture was going to look like, so there weren’t individuals talking over one another. It was structured in a way.

[18:32] It seemed organic, but it wasn’t necessarily that organic. When we got to the sections where we broke into small groups, we also utilized the phone. We did the old school conference calling, where there’s a phone in the middle of the room.

[18:51] Individuals are on the speaker. There are four eager students leaning in on the phone on our side where I could see. Then on the side of the correctional facility, the warden would create the same spaces there. It would be for women there.

[19:06] It would be a calling conversation. I created it in a way that you could use technology in the same ways that individuals are incarcerated can only communicate. We know that when you’re incarcerated, you only have mail, you have calls, and you have visits.

[19:23] The calls were the opportunity to utilize that. In the federal system, they’re also able to use technology in that way here and there. They have to pay for it, so it’s not as often. We merit it in that way.

[19:37] Once we got into about class three, the students knew already. We check in, “How are you doing today?” They will listen to every one talk. When they jumped into the going from inside to outside student, they were very respectful about waiting until someone completely finished their sentence.

[19:55] That was where harmony started coming in. It was like we had to hone in with technology and submit to it in a way that allowed it to really work best for us. That meant that we just needed a lot more structure than what you would have in a classroom where individuals are talking over one another, or jumping in, or holding their hand up for three hours.

[20:20] Where this way, you critically think about what you want to say the night before. If someone says something, you’re taking notes and writing it down. When your turn comes, you’re sharing that.

[20:30] At the end of the GroupMe sessions, the part that I really liked the most was an opportunity for individuals to open‑share. Really, there was this opportunity for a Howard student to jump in and say, “Hey, this is kind of what I’m feeling about it,” and then an incarcerated student.

[20:47] We would do that for about, I want to say, 20 to 25 minutes, and it worked. Anything beyond that, absolutely not. After 25 minutes, it’s like with any class. It’s like, “OK, we’re gonna take a short break.” In those instances, it’s a yes and a no.

Derek: [21:03] It sounds like the students got to have really meaningful interchanges with each other, but there was a level of structure and intentionality that you might not need if everyone was in the same room. You might be able to use social cues and body language to navigate some of that.

Bahiyyah: [21:17] Absolutely. You would be able to see a hand go up. You’re able to see somebody shifting back and forth in their seat. In the end, when we had what I call the open mic ‑‑ I call it an open mic ‑‑ what they were able to do was to say, “Oh, I’m so heated over this.”

[21:36] You could get that emotion out, but there was a time and space for it, where in a regular classroom, you can just say whatever. Even if it dovetails the conversation in a way that it’s not necessarily supposed to go, it’s that way.

[21:49] You find with technology, I got through all of my lecture information. It’s like everyone has a place in terms of speaking about what’s going on, and it meant that it was a lot easier for me to stay on topic.

Derek: [22:04] You also mentioned the virtual tours. Did you create those? Did you find those? Where did those come from, and then what role did they play in preparing students for their actual visits?

Bahiyyah: [22:14] Google went in and actually just sat down for three hours one day and just looked up virtual tours for Connecticut and New York. I went through each and every one of them and really took my time and took notes.

[22:29] Some were better than others, in my opinion, as it related to things that I’ve done. I just put, maybe, five or six up there and then also said to the students, “Hey, if you want an extra credit point, identify, maybe, one in your town, or in your state where you’re from.”

[22:45] Now, I have a whole folder full of virtual tours and students talking about what it was like to see this facility in Arizona compared to a facility in Mexico. Really, a great opportunity. What I’ve decided to do now, where I’ve become this technology guru on the campus, is create my own.

[23:08] I have a videographer now and a partnership with the Department of Corrections, really having the cameras roll, and follow me, and saying, “This is the way that you will enter into this facility. You’ll have to make sure that you go through these lockers.” Creating it so that I could totally put the class almost all the way online in the beginning.

Derek: [23:35] Your students, since you were working with a partner in West Virginia, they weren’t able to visit regularly. It sounds like they would visit occasionally, so you still had some of that in‑person experience.

Bahiyyah: [23:46] What I wanted to do was, we did have a couple of grant funds that we pulled in. If you’re using GoToMeeting, each bus ride was $3,000. Multiply that by 15 weeks ‑‑ you could do the math there ‑‑ it goes to zero with GoToMeeting.

[24:02] It allowed me to be able to be a little bit more creative. What I decided to do was I looked at the research. The research around mass incarceration identified that 70 percent of the individuals who are incarcerated don’t get visits.

[24:15] That means that you’re not going every week. Really, the Howard students were very privileged. Then when you think about an Inside‑Out class, those students who are in these universities have more access to incarcerated individuals than their own family members just by virtue of the privilege of going to a university or college.

[24:35] I wanted students to understand that. I didn’t want to bring them every single week and show this superficial relationship. Although it would have been great for the class and bonding, it’s unrealistic in terms of how to help the population that’s dealing with it. They went once a month.

[24:51] It was so interesting, because as they read the literature, they’re just like, “One of the grandmothers in the literature gave up on visiting, because it just became too expensive.” The students were just like, “Oh, my God, I feel the same way. It’s such a long ride, and you have to prepare yourself in advance.”

[25:09] I’m just like, “Remember the article we read? What about that parent, and how can we create a program or some sort of a service to alleviate that so that we could bridge the bonds between those who are incarcerated and their family?”

[25:20] It was really realistic, where once a month, out of the four classes they would have, three of them would be using technology in various ways over the phone, or GroupMe and Skyping in.

[25:32] Then that one day, we would meet at six in the morning at Crampton Hall, outside of main campus. We would all board a bus, and we would go to have a session with the women face‑to‑face.

[25:43] You would not believe the bonding in terms of bridging and building relationships. It’s just like when you have your BFF on your social media. When you finally get to meet, you’re like, “Oh, my God. I’ve been following you all this time.” It feels like you’re more connected than you really are.

[26:04] That actually happened, and it allowed for the conversations in person literally to be…There were no bars. There was nothing that held them back. They shared any and everything.

[26:19] It built trust in a way a lot quickly than it would in your typical Inside‑Out class where they’re waiting to hear what you’re talking about. They’re looking at what you’re wearing and how you’re dressing.

[26:32] When you’re over the phone and having a group conversation and then you’re Skyping in or you’re texting in through GroupMe, you have no idea what I’d look like. There is no stigmatizing me as it goes to what I look like.

[26:46] You may know my gender from my voice, but you have no idea what my race is. It built barriers and ripped down walls and ways that was just like, “I wasn’t sure why the Inside‑Out model was just like, ‘Are you sure you’re gonna be able to get that transformative effect?'” It’s just like, “Absolutely. Absolutely.”

Derek: [27:05] It’s interesting. I know when I’m working with my colleagues at multi‑institution research projects or something, what I’ve learned is often the group works better if you meet face‑to‑face first at a conference or a gathering. Then you go off and go online, and you get the work done.

[27:23] It sounds like in your case, it was just the opposite. It was the online interactions that prepared students on both sides for a more meaningful face‑to‑face encounter when it finally did come.

Bahiyyah: [27:35] Think about it. You’re going to go into a supermax facility. Look at the way they project things on the media. The first couple of classes, they’re sitting and looking around. You don’t know how to take it in.

[27:49] Over the phone, you’re just having a conversation. If someone knows how to engage in this conversation like, “Oh, wow. This is…” When you go into the facility, it’s just like, “Wow, this is a facility.”

[28:01] Then you hear that familiar voice that you spoke to for three hours over the phone. The way we use technology now, that is ridiculous.

Derek: [28:10] [laughs] Who does that?

Bahiyyah: [28:12] Who does that anymore? It created the classroom space that you want. It was economical in the end.

Derek: [28:26] You mentioned the Blackboard and the GroupMe, these virtual spaces where students could connect with each other. Were the inside students part of those spaces as well? Did they have the technology access to interact with the outside students through texting, through GroupMe, or things like that?

Bahiyyah: [28:43] No. One of the requirements of the Inside‑Out Program is that you maintain semi‑anonymity. You only use a first name basis. You can’t exchange any contact information. That’s for the safety on both sides.

[29:02] Correctional institutions, when they let us come in, it’s like, “This is educational, period, and you’re not building any of those kind of like relationships.” The way that we worked around that was that the GroupMe was solely for the students at Howard University.

[29:17] Then on the side for the correctional institution, they created a network where the Educational Department would take sheets of paper from any of the incarcerated individuals throughout the week for things that they…

[29:31] That was their way of texting, so to speak. They would write it down, give it in. In real‑time, they would scan it over as a PDF to me, and then I would be able to send the message back.

[29:41] It took more work on their end in order to do that. Then the students who were incarcerated actually added me to their Internet email interface. They’re able to engage in three or four emails or so out of the week, depending on how much money they have on their commissary.

[30:01] As an instructor, I was able to go back and forth. I started as the liaison between the technologies used on the campus with the students and then created that feedback to them.

[30:13] I would always give the updates on a weekly basis to say, “Hey. One of the conversations in the GroupMe that continues to go on is they wanna know why these particular policies in an institution have been around for so long and aren’t changing.”

[30:28] When we would come back together, it was like everyone was on the same page, although they didn’t all use the same technologies. Now, what you’re starting to see at the institution that I’m in now, the DC Jail, I’m really excited about is they have tablets.

[30:44] It allows for the incarcerated students to send me direct messages as an instructor, and I can respond. You can have an app up there that allows just for classroom conversation and dialogue. I could upload all of the readings. Amazing technologies that they’re using now. I’m so excited about the future of where this can actually go.

Derek: [31:05] That sounds awesome. It sounds like more options for connection, for interaction. That’s really great. What advice would you give to a faculty member who’s interested in getting involved with Inside‑Out?

Bahiyyah: [31:20] Go to the website, and look up the program, and see when the next training is. Sign up whenever you can, regardless of if you know how you’re going to use it.

[31:32] You may not even see yourself as a biologist going into a facility and teaching biology, but go and allow it to open up your mind. You really will be surprised.

[31:42] At the end of the training, you utilize that time to be able to create your own syllabus, so to speak. It allows you to get the 15‑week curriculum, so you could see exactly how it works.

[31:55] Then one of the most amazing parts is you go into a correctional facility three days out of the five days, and you engage with incarcerated individuals in the same way that you would for a class you teach, even if you never teach a class.

[32:11] I was trained in 2007. I didn’t get the first class up and running until about 2013. It took a while to get it going and for me to be teaching it on my own.

[32:23] I still learned so much. It helped me as it relates to this phenomenon of mass incarceration in the United States. I would say that the first step would be to check out the website.

[32:36] They have podcasts that they do that are absolutely amazing with incarcerated individuals, formerly incarcerated individuals, instructors. They have a list of all of the correctional facilities across the world that they’re partnering with. They have the instructors who are up, and leaving quotes, and talking about it.

[32:54] You could spend a nice amount of time just on the website. I think that would be the best start. Then to ultimately reach out to someone in your state that has a program up and running.

[33:06] Have coffee, Skype with them, and talk to them on how you may partner or how you may bring something like this to your university. Then thirdly, I would say show an Inside‑Out video. Talk with it in one of your classes and see the excitement and the interest as it relates to the students. That’s always something that’s motivating.

Derek: [33:28] I want to come back to the technology for a second. It seems like you’ve approached your Inside‑Out courses very differently because of your technology use. Has that changed how you teach some of your more traditional courses at Howard?

Bahiyyah: [33:45] Absolutely. Since I’ve done this class, it’s so interesting that I flipped literally 10 of my classes today. I literally beefed up the online components to the point where just this summer I taught a corrections class online.

[34:03] When I read the reviews, I was blown away. The students were just like, “I thought this was gonna be a summer session. I wasn’t gonna get the Dr. Muhammad experience, and it was amazing.”

[34:14] They’re like, “We did a tour online. I had no idea that there were virtual tours.” They’re like, “I really read all of the information.” I upload amazing videos and interviews from TED talks that dig at the hearts of the students.

[34:30] Then I also allow the students to introduce themselves to one another, create cool videos that they post. The online experience is almost mirroring what would happen in the classroom. I love, love, love that I’ve been able to do that.

[34:48] It’s really forcing me. Also, now I’m speaking to colleagues in my department to say, “Hey, you guys should sign up for A2 Teach which gives you $3,000 stipend, which is not a crazy amount, but in the summer to help you flip your classroom.”

[35:07] 30 percent you can flip, 60 percent, 100. I started at 30. Now, I’m at 100 percent, flipping every class. It frees up so much space for writing. I’m just like, “This is amazing.” I’m working on a book now and a couple of chapters.

[35:23] Then it keeps you hip. It keeps you for yourself. I feel like it keeps me healthy, and excited, and really quick. When things are posted or students have issues, I could address it in real‑time. It gives me more time later on because it doesn’t become an office hour visit or a two‑hour conversation that could have been a one‑second text.

Derek: [35:48] We have a question we ask all of our guests. We focus a lot on the podcast about digital educational technology. We’ve mentioned a lot here today in our conversation. What’s one of your favorite analog educational technologies?

Bahiyyah: [36:04] That is such a good question. I don’t know if this would count, but the voice diaries that are on the iPhone. I’ve been doing digital diaries. The students are able to pull up their iPhone, click the app for the voice diaries, and in real‑time say the date, say the time, the topic of the class, and go on.

[36:30] I’ve been getting students, when I transcribe what they send back to me, 7 to 10 pages. It’s hard to get them to even write a page sometimes even when it’s a self‑reflection. They’re going on and on.

[36:47] That technology, they pull it up even without WiFi, even without anything. They’re storing this digital diary that I can then put into my research, my pedagogy.

[36:59] Then they also, when they graduate, can go back and say, “Oh, my God. In 2015, I was crying every day after that. I’ve become so strong as it relates to these issues.” I would definitely say the voice diaries, some of those.

Derek: [37:20] I would call that digital, but I will accept your answer because it was so great. [laughs]

Bahiyyah: [37:26] What are some of yours?

Derek: [37:30] Honestly, you answered the question earlier when you mentioned the phone. Technically, it may be some Voice over IP, digital kind of thing, but it’s a very analog technology. We’ve had conference call capability before we had an Internet. That analog piece and the community that it facilitates around something as simple as a phone call.

Bahiyyah: [37:54] It’s interesting that you said that, because one of the things that the inside students, the incarcerated students talked about was how using the phone in an educational way changed the way they communicated with their children.

[38:09] They started sending the readings home to kids. Typically, they would have these conversations. It’s like, “What happened this week? What is your mom doing? Who was she dating now?”

[38:19] It’s more of looking at the child and the child being an informant. There were no educational components where they started to ask and mirror exactly how the worksheet conversation went outside of the class.

[38:33] The warden ‑‑ in correctional facilities, they have to record every call ‑‑ she mentioned how the dynamics of the conversation over the phone completely changed. They’re talking about college and what do you want to be when you grow up. They did check‑ins when they first got on the phone.

[38:52] It wasn’t like they just jumped in, not being able to talk to one another for a whole week. It was like they had patience with themselves in the same way they did with the class. They asked about, “What is your homework like, and what are you doing?”

[39:05] The conversation was more double‑sided than one‑sided. The kids could talk, and you can hear from them. Then they would go to the parents. I was just like, “Wow.” Also, it’s interesting that the Howard University students were just like, “I gotta call my mom. I need to call my grandma.”

[39:25] They don’t have the apps and they’re like, “I need to be on the phone.” If there was a way where they were able to blur everything out, they’re on these phones for dear life. It’s like you’re trying to hear. There was no dropping a call. As long as you have it plugged into the jack, it’s going to be there.

[39:47] It reminded me of when I was growing up. You’re on the phone with your friends and you’re just so excited. There was no technology. Things were real. There was no fuzziness to say, “Hey, can you hear me? Can you hear me? Can you…?” It was none of that.

[40:03] It’s interesting, because you don’t even think of that. I don’t even think in that way anymore. I think in a technology kind of way. If I go back to it, I definitely know that the incarcerated students would say that for them it would have been the phone.

[40:18] For the students at Howard, they went back to some of those old school traditions and actually sometimes picked up the phone and said, “Hey, Mom. Thank you for this and thank you for that.” It’s amazing how they had three‑hour conversations without a dropped call.

Derek: [40:36] That’s great. [laughs] Thank you, Bahiyyah. This has been really rich.

[40:41] [background music]

Derek: [40:41] I’ve enjoyed this conversation today in hearing about all the ways that this program of yours works, and how you use technology, and the impact that it has on your students. Thank you so much for sharing with us.

Bahiyyah: [40:53] Thank you so much.

Derek: [40:55] That was Bahiyyah Muhammad, assistant professor of sociology and anthropology at Howard University. I enjoyed my conversation with her and I hope you did, too.

[41:04] Bahiyyah’s stories about how course‑related telephone calls affected both sets for students was inspiring. It reminds me of the impact our educational choices can have on our students’ lives outside the classroom.

[41:15] For more on Bahiyyah Muhammad and the Inside‑Out Prison Exchange Program, follow the links in our show notes. You’ll find those show notes on our website, leadinglinespod.com, where you’ll also find past Leading Lines episodes with full transcripts.

[41:28] We’re on Twitter and Facebook, too. Just search for Leading Lines Podcasts. If you have a moment to leave us a rating and review on iTunes, that would be great. That helps other people find the podcast.

[41:39] Leading Lines is produced by the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching, the Vanderbilt Institute for Digital Learning, the Office of Scholarly Communications at the Vanderbilt Libraries, and the Associate Provost for Education Development and Technologies.

[41:50] This episode was edited by Rhett McDaniel. Look for new episodes the first and third Monday of each month.

[41:55] [background music]

Derek: [41:55] I’m your host, Derek Bruff. Thanks for listening.

Transcription by CastingWords